John Donohue

Jim Grant was/is the only senior official I ever heard discuss the Great Leap Famine as it now seems to be called. Jim was leading a large staff meeting. It must have been large if a P4 supply guy was attending. An aside/a learning moment for me, Jim Grant always invited low ranking unimportant people to meetings. He always used these sessions to teach his staff.

This around 1988/89 before the children’s summit, and I think in the Labouisse room so after the 866 building. I recall no one in the room knew a thing about the famine he discussed, it was well hidden.

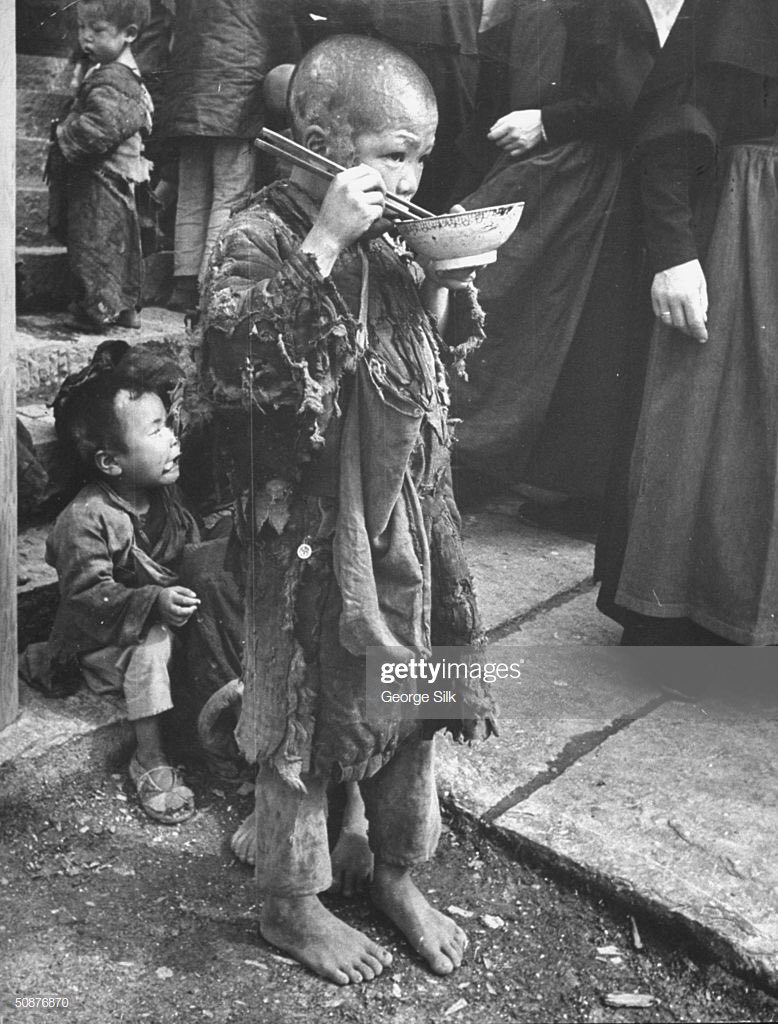

I was thrilled to be present, and I listened carefully to his narrative of “the worlds’ greatest famine.” That’s how I remember his introduction. Jim’s key point wasn’t the size of the famine, but the cause. It was induced by cowardly bureaucrats. Every administrative level was afraid of reporting the truth to Mao in grain harvests, because they would look bad.

Mao decided to change the tax code and base grain collections on the harvests being reported. Mao either didn’t know or didn’t care that those reported harvests were fake. He instructed the grain tax collections be delivered based on the reported fake numbers. Then none of the thousands of officials had the courage to tell Mao, and the other higher ups that the reported bumper harvests were fake. Bureaucratic cowardice induced a famine that Jim believed killed 20 million people. At that time I was reading/thinking about Ethiopia, the Irish famine and Amartya Sean’s great book on famines. Thanks to Jean Wasselin, I had seen a small part of the mid eighties famine in Ethiopia. My take away from Jim Grants tiny seminar on the great famine of China was the importance of integrity and courage in governing. Jim seemed always trying to teach his people and his clients that governing required independence and willingness to confront illusions.

Accurate history and reporting truth to the boss remain benchmarks of governance.

Hope you’re well, John

Read article here

Xi Extols China’s ‘Red’ Heritage in a Land Haunted by Famine Under Mao

By Chris Buckley Sept. 30, 2019, 5:00 a.m. ET

|

| A farmer in Gaodadian Village in the Xinyang region of Henan Province. 60 years ago, over half of the villagers in Gaodadian starved to death as a result of Mao’s Great Leap forward. Gilles Sabrié for The New York Times |

XINYANG, China — Harrowing memories of China’s revolutionary past hang over the rolling wheat fields and scattered villages where the Communist Party’s leader, Xi Jinping, recently visited to commemorate 70 years since Mao Zedong founded the People’s Republic.

Yet not all who died in the Xinyang region during Mao’s tumultuous era were honored during Mr. Xi’s political pilgrimage. Who was remembered, or overlooked, put in sharp relief his authoritarian recasting of Chinese history.

Mr. Xi bowed in tribute at a memorial for 130,000 fighters from this area in central China who gave their lives for the Communist cause. The estimated one million peasants who starved to death in Xinyang after Mao’s Great Leap Forward spawned the biggest famine in modern times went unnoted in official report sabout the visit.

Sign up for The Interpreter

Subscribe for original insights, commentary and discussions on the major news stories of the week, from columnists Max Fisher and Amanda Taub.

The pageantry of the 70th anniversary reveals how thoroughly the party has rewritten China’s past to reflect Mr. Xi’s turn to communist traditionalism — what he calls reviving the party’s “red genes.” He offers an unabashedly triumphant vision of China’s past, and its future. It is a patriotic message that resonates with many Chinese, even in Xinyang, a region of rural counties and towns that suffered greatly under Mao.

“This red land was hard won and paid for with the fresh blood of tens of millions of revolutionary forebears,” Mr. Xi said when he honored revolutionary “martyrs” in Xinyang in mid-September, according to an official account. “We must always recall where red power came from and cherish the memories of our revolutionary martyrs.”

[Here is how China is preparing to exalt President Xi as its unassailable leader on National Day.]

In his seven years in power, Mr. Xi has acted on the belief that to control China he must control its history. His administration has molded textbooks, television shows, movies and museums to match his narrative of national unity and rejuvenation under iron party rule.

Under him, the Communist Party has promoted revolutionary nostalgia and played down the strife of the Mao era. The anniversary celebrations, which culminate on Tuesday with a military parade in Beijing, have reinforced this rosy depiction of the past 70 years as a near-uninterrupted march of economic and technological progress, enshrining them through oversize floral displays in Beijing. On Monday, Mr. Xi paid his respects to Mao’s preserved body in a mausoleum in Tiananmen Square.

Mr. Xi’s recasting of China’s history has left less and less room to reflect on traumas like the tens of millions who starved to death across the country from 1958 to 1960. That worries scholars who believe that the calamities of that time still offer lessons for China.

In the run-up to the 70th anniversary of Communist rule in China, the country’s leader, Xi Jinping, visited a monument to revolutionary martyrs in the Xinyang region.Xie Huanchi/Xinhua, via Getty Images

Harvests fell drastically short of the miraculous yields that officials had promised in the Great Leap Forward, a feverish campaign to propel China into communist plenty. As hulking collectivized farms failed, the government seized grain from peasants who were accused of hiding supplies. Starvation spread. So did persecution of peasants accused of resisting grain seizures.

Xinyang suffered worse than nearly any place in China. Out of eight million residents, about one million died of undernourishment and other abuses, according to secret official reports at the time.

In Gaodadian Village in Xinyang, two mounted stones stand etched with the names of 72 people who starved to death in this settlement of around 120 residents. The memorial, half hidden among bushes, is the only one around here, or perhaps anywhere in China, for victims of the Great Leap famine.

Elderly farmers nearby recalled famished parents who died after eating grass that clotted their intestines; swallowing weeds and tree bark to stave off hunger; tearing open pillows to boil and eat the wheat husks inside; and occasions of cannibalism when ravenous villagers cut flesh from corpses.

“This will let them know about this terrible lesson, so that it cannot be repeated,” said Wu Yongkuan, 75, a retired village accountant who built the memorial 15 years ago mostly to honor his father, Wu Dejin. He died in the famine after being denounced by officials for asking for more food for fellow villagers.

“Their voices and faces remain with us, in the embrace of eternity,” says a dedication written on the side of the names. “Dignity and decency always resplendent, models of all that is worthy.”

Still, Mr. Xi’s patriotic telling of Chinese history attracts quite a few admirers, especially in rural areas like Henan Province, where views tend to be more conservative. The notion of a “good ruler” in Beijing — a leader whose noble intentions are thwarted only by venal local bureaucrats — runs deep. People can nurse bitter memories of hardship under Mao while still revering him as a great revolutionary who liberated China and its peasants.

For decades, the party has reinforced the theme that even in the worst of times, Mao and other top leaders in Beijing were on the side of the people. Reports and investigations mostly shielded them from public criticism. After Mao died, Deng Xiaoping pressed to ensure that he was not swept into the dustbin of condemnation like Stalin had been in the Soviet Union.

In Xinyang, many residents blamed the famine on wayward local officials, especially Lu Xianwen, the party secretary of Xinyang who was accused of hiding the mounting deaths. “It wasn’t his fault,” Mr. Wu said of Mao. “The central leaders didn’t know.”

Most Chinese scholars who have studied the famine and other upheavals are much less forgiving of Mao. Local officials who concealed the growing disaster came under immense pressure not to risk stirring Mao’s wrath.

The question of Mao’s culpability remained politically charged, said Zhu Jianguo, a former journalist in southern China who has written about the famine in Xinyang. “There’s an ancient Chinese saying: If the many regions commit offenses, the responsibility lies on my person,” Mr. Zhu said, citing words supposedly uttered by an emperor. “How could this have nothing to do with him?”

While the Communist Party has long constrained historians from delving into its past, Deng and later leaders allowed some debate. Books and academic papers examined the Great Leap Forward. Former officials who had enforced Mao’s policies at the local level wrote pained memoirs.

In 2016, a county in Henan Province erected a gold-colored, 120-foot statue of Mao. Officials tore it down after criticism spread of the garish sight.European Pressphoto Agency

Exposing the party’s historical setbacks has become increasingly unwelcome under Mr. Xi.

Soon after he was appointed Communist Party leader in late 2012, Mr. Xi spoke of a “China dream” of national strength rising after centuries of foreign subjugation. He denounced “historical nihilism,” the party’s term for accounts of the past that dwell on its errors.

Although he was the son of a party veteran persecuted by Mao, Mr. Xi sought to shore up Mao’s reputation. He warned officials in 2013 to take heed of the unraveling of the Soviet Union, when liberal historians dismantled its revolutionary heritage.

“Why did the Soviet Union disintegrate? Why did the Soviet Communist Party collapse?” Mr. Xi said. One important reason, he said, was that its leaders had allowed Stalin, Lenin and Soviet history to be denigrated.

“There’s a lesson in that for us,” Mr. Xi said.

Access to archives came under heavy restrictions in recent years. Party officials engineered a takeover of a magazine that specialized in unvarnished accounts of party history, turning it into a tame publication. Pro-Mao writers have argued in party-run journals that the Great Leap famine was not nearly as bad as previous scholars found, including in Xinyang.

“Critical voices have been silenced,” said Hong Zhenkuai, an independent historian who has challenged the denials of catastrophic famine. “The danger is that if you don’t reflect on the errors of the past, don’t acknowledge the mistakes that were made, you’re incapable of drawing warnings from history.”

Outwardly, few provinces in China would seem more welcoming to Mr. Xi’s traditionalist message than Henan, where he visited ahead of the anniversary. Many villagers, including Mr. Wu, here said they admired Mr. Xi as a strong leader in Mao’s footsteps, and they often hang portraits of both leaders on the walls of their homes.

In 2016, a county in Henan erected a gold-colored 120-foot statue of Mao. Officials tore it down only after criticism spread of the garish sight.

But Henan’s modern history is also scarred with upheavals.

Apart from war and famine, there were huge floods in 1975 that killed tens of thousands, when poorly built dams collapsed after storms. In the 1990s, the province had an outbreak of AIDS among tens of thousands — some experts say many more — of poor farmers after officials let H.I.V. spread through a trade in tainted blood. Farmers who sold their plasma were given transfusions with the leftover blood products that had often been infected through poor hygiene.

Mr. Wu’s son, Wu Ye, 51, helped his father build the famine memorial in their home village. He said he grasped the enormity of the suffering only after he moved to the United States and read a Chinese-language book about that era, “Man-Made Catastrophe,” published in Hong Kong in 1991.

“On the internet there’s all those people who say that it’s nonsense, that so many people couldn’t possibly have died,” the younger Mr. Wu said in a telephone interview from Buffalo. “I wanted to somehow prove that this happened.”

In Xinyang, memories of famine survive in family lore. On a recent visit, villagers in their 60s and 70s paused to count and name parents and siblings who died 60 years ago.

“Nowadays we have enough to eat, but back then we went for days and days without anything,” said Chen Xueying, a 71-year-old farmer who paused from picking beans to describe how she watched her mother and a sister die in the famine. She teared up.

“We suffered a lot,” she said. “They’re all gone.”

Amber Wang contributed research.

Comments

Post a Comment

If you are a member of XUNICEF, you can comment directly on a post. Or, send your comments to us at xunicef.news.views@gmail.com and we will publish them for you.