The Beach

At dawn I woke up to a booming noise that seemed to be everywhere. I sat up and looked over the dunes to the sea. A black man too beefy to be a Somali set a red torch on the bank to our right; he now jogged along the water towards our left. I intercepted him to ask what was going on.“Hey buddy! We are having a little exercise. No need to move out. When the tanks are coming in, just stand up and wave your arms, so they don’t roll over you.”

I had signed up as the teamleader with the German Emergency Doctors (GED), in Northern Somalia, in 1982. We had a night on the Beach, when the US Navy decided to🔗impress their new-found Somali friends with a show of force, right at our spot.

Not wanting to be in their way, we moved our belongings beyond the flare and watched the spectacle unfold from the roof of our Landrover. A little later, I spotted the regional head of the Somali army in the distance behind us, on some purpose-built platform. We happened to be standing right between him and the action. Certain that he had trained his binoculars on the German doctors and nurses instead of the marines digging into the sand, we moved a few hundred meters on. The marines drew ever larger circles to come close and waved enthusiastically towards our group, which remained thoroughly unimpressed.

The US Marines on the beach near Berbera, Somalia 1982. Watch the carbon footprint.

Northwest Somalia

The Refugees

As a result of the Somali invasion of and defeat in the Ogaden war, many hundred thousand Somalis had fled from the Ogaden Region to Somalia. They subsisted in more than 40 camps, of which eight were in North-West Somalia.

Three camps were medically looked after by the German Emergency Doctors (GED), comparable to today's Medicines Sans Frontiers. There were also SCF, Oxfam, Worldvision. Everyone supported the Refugee Health Units (RHU) run by the Somali Ministry of Health.

The iconic Green Book of 1982, issued by the Somali RHU.

Adhis Adeys Refugee Camp, 1982. The prefabs are the health centers, the white tents housed the GED.

Most volunteers stayed three to six months. Gabi had already been there for one year when I arrived, and together we remained with the GED for another two years.

Feeding Center

At the Feeding Center

Primary Health Training/Messaging in a refugee camp

The GED had its own drilling rig to provide water in the 'GED camps'.

Tapstand in a refugee camp

Christian Pflüger, who also joined UNICEF later on, and myself cleaning a borewell.

Hargeisa Hospital

Entrance to Hargeisa General Hospital, 1983

A visit from GED headquarters, Hargeisa Tuberculosis Hospital

The GED undertook to renovate and reequip the hospital, ensure regular medical supplies and train staff. Some of the few Somali doctors were jailed for organizing self-help campaigns. Gabi took charge of the outpatient clinic; for this, she learned to speak Somali.

Chinese Aid

China had sent a team of surgeons, a gynecologist and an anesthetist, who could only communicate through their minder/ translator. They had their own anesthetics, but the GED helped them with dressings, drugs and equipment. The team rotated every two years, and worked for very little. Their house in Hargeisa did not even have a refrigerator. One surgeon died of a heart-attack in Hargeisa, and was buried there.

The 'head office' of the German Emergency Doctors in Hargeisa, 1982 - without telephone, internet, telex or radio.

Taking a break to have a close look at the Berbera Blackhead, the quintessential Somali sheep. Much of the income of Somaliland is derived from selling camel and sheep to Saudi Arabia for the annual Haj, with as many as 10,000 heads of sheep and goats sold daily and shipped through the port of Berbera.

Managing the influx of so many livestock into a single port is a major challenge, due to the need for water and feed. The cattle migration to Berbera led to Somalia becoming one of the first countries in Africa to adopt mobile phones in the early 1990s , despite having no government. With telephone lines routinely looted for their copper, cell phones proved to be the only viable way for traders to coordinate their exports.

Logistics

As of 1982, all medical and technical supplies for the refugee camps and the Hargeisa Hospital were sent from Germany to Djibouti, from where we picked them up with our own second-hand M.A.N. truck, once every three to four months.

For reasons I can no longer explain, the truck had only one music casette, which kept running in continuous loop. Click on the button above, turn the volume up and continue reading while the music is playing.

Breakdowns were common. Hint: it is always the dirt in the fuel.

One tends to think of deserts as dry and sandy. Droughts happen. But a desert can also be wet and bottomless.

Onto Lac Assal

Once Gabi and I took our Landrover to Djibouti, and we decided to take one day off to circumdrive the Gulf of Tadjourah, on our own. Lac Assal is the deepest point of Africa, with 154 Meter below sea level, deeper than the Death Valley in California. At that time there was only an indistinct trail leading through the most remote, desolate, inhospitable and extremely rocky terrain.

It happened the way it had to. As the night fell, the axle of our battered Landrover broke (for experts: the U-bolts snapped), in the middle of nowwhere, 30 kilometers away from what could be considered a road.

We managed to fix the damage with the proverbial piece of string, and after an uncomfortable night continued the next morning. The rope was good enough to take us back to civilization.

Getting Married

Gabi had looked after newborn Maryan from her first day. It took five years until the adoption was legalized by a Somali court.

Participatory WASH

During five years living in Somalia, I saw Mogadishu only twice

We later managed to get married in Kenya, but celebrated in Hargeisa.

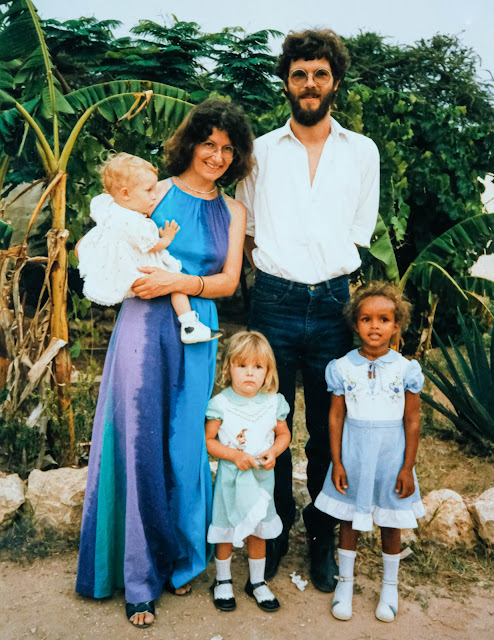

Wedding party in Hargeisa, Somalia, 1982

Everyone dressed up for the party, and also the Chinese doctors came to celebrate.

Clouds gathering over Nasa Hablod - the two breasts mountain, the landmark of Hargeisa

The GED project was morphing from emergency relief into a development intervention. We managed to reduce our personnel from initially 30 doctors and nurses to four of us supporting the Hargeisa Hospital, which covered the entire NorthWest Region. But the head office told us to shut down.

Money was not the problem. It never is. Rather short-sightedly, the GED headquarters viewed any involvement in development beyond its strategic role and focus.

Meanwhile, UNICEF was getting serious about its North-West Integrated Social Development Programme (NWISDP).

UNICEF and TEMO

In 1984, UNICEF asked me to temporarily look after the Hargeisa Transport and Equipment Maintenance Organization (TEMO), which was part of the NWISDP. The previous UNICEF official had abandonned his post, insisting that goats were to blame for the destruction of the Somali environment and economy.

A special moment: Exchanging our trusted GED Landrover for the rather new UNICEF Landcruiser. Maryan and Tini, recently born in our home in Hargeisa, were delighted.

The North-West Integrated Social Development Programme (NWISDP) was a boastful title for an assemblage of discrete projects involving primary health care, nutrition education, water, and sanitation (no education). The level of integration was demonstrated by the UNICEF health officer having ordered Landrovers, the UNICEF water engineers Toyotas and Fiat trucks, the UNICEF administrators Suzukis, and the Italian donors wanted to buy us Pandas. Together with the existing government fleet of decrepit Landrovers, TEMO was to keep 100 vehicles of all sizes and ages on the road, and to look after all manner of drilling rigs, generators, motorpumps and, most importantly, the UNICEF office photocopier.

TEMO had about 25 staff, including apprentices and specialists for everything. Everyone took pride in what they were doing.

Our stock of spare parts was worth more than one million Dollar. UNICEF had just introduced Wang Computers, but not for TEMO. When after six month I was offered a regular contract, which I had to sign in Geneva, I bought myself one of the first available personal computers (an Amstrad with 0.25 MB memory) to digitze the TEMO inventory system.

Mohamed, our store manager. We did not loose any spare parts, nor any workshop tools.

UNICEF paid a basic local salary (a tiny fraction of the UN General Service scale) and would not even provide workwear. So I organized our TEMO T-shirts on my own.

TEMO forced regular preventive inspections on the cars of all reluctant colleagues and officals, and 'created evidence', as it is known today. Much to the chagrin of our british UNICEF colleagues, we established that a Landrover consumed several times more spare parts than a Landcruiser.

The 'integrated' programme made slow progress. Experience from elsewhere in the world was not easily transferred to Somalia.

Near the Ethiopean border. For more than two years, UNICEF and Abdul Awal tried to find water by drilling close to 300 Meter deep.

Tini checking progress at Balli Ahmed, which was meant to become an artificial lake fed by rainwater run-off. It is not clear whether it ever functioned as planned.

Around 1986, auditors endeared themselves to me when they recorded - confirming my private observations - that the result of UNICEF's three-year sanitation program were three unused VIP latrines in a single village resembling "pitiful monuments".

Life in Hargeisa

The economic and security situation in North West Somalia continued to deteriorate.

Our house in the middle of Hargeisa. Soon the water supply stopped and we built the pictured concrete tank, which was filled once every three months. Over time, electricity was only available for three hours a day, at 70 instead of 220 volts. At night we could see the light bulb, but nothing else.

Checkpoints sprung up everywhere, manned by drug-crazed, Kalashnikov-wielding youngsters with bloodshot eyes. One night - though she claims not to remember it - Gabi demanded in Somali that on-comers be addressed more politely, leaving the youth bewildered but accommodating.

The vultures used to sit menacingly in the eucalyptus tree in front of our house, watching over the almost nightly gunfights between the army and gangs for control of the lucrative khat trade. Khat is a mild drug that makes people more talkative, causes euphoria and delusions and, above all, is a grandiose waste of money.

Josi was born in our home in Hargeisa when the town was in the grip of a Cholera epidemic and completely quarantined for three months. We managed to smuggle our aunt into town for the event, who as a retired midwife was coming to help.

The green folder is the 1986 version of the UNICEF Programme Policy and Procedure Manual - also known as the Book D. I suspect that I was the only staffmember reading it, as nobody ever complained when I kept it at home.

I found that the manual had little relevance to the management of UNICEF interventions. One example were the required vehicle loan agreements, that only served to muddle up ownership of the programmes, removed accountability and let to the abuse that they were meant to control. I therefore proposed a clean handing over, and designed a template for the logo that was meant to be applied. Tini was fascinated.

In mid 1987, TEMO was ready to be handed over to the Government, and so it happened. Exactly on the day, five years after I arrived in Somalia - and six years after Gabi had come - we quietly left Hargeisa for Djibouti, on the tracks we knew so well.

Somalia was rushing towards the abyss, and the story towards its end. Civil unrest broke out; Hargeisa was bombed in early 1988. The UNICEF office was evacuated. TEMO was destroyed and looted, the staff dispersed.

Our next stop was Khartoum, which in comparison to Hargeisa we considered cosmopolitan; and where we soon after got to crank up 🔗Operation Lifeline Sudan.

Post Scriptum: Somaliland has declared its independence from Somalia in 1991 and has since enjoyed relative peace and stability. In 2017, the Economist considered Somaliland to be 🔗east Africa's strongest democracy. Another successful election took place in 2021. Still, Somaliland's independence remains unrecognized by any member state of the U.N. or any other international organisation. Widely used mobile money was introduced in 2009, well before Kenya's M-PESA. The port of Berbera has been upgraded with the help of the U.A.E.. It has become one of the most successful ports of sub-Saharan Africa. I recently discussed the role of the UN in Somalia with Dr. M. Warsame - one of the architects of the Somalia RHU and Primary Health Care system in the '80s. Asking about the key drivers of development in Somaliland, his response was unequivocal: the private sector.

*****

Other photo-stories by Detlef:

- Lunae Montes - a journey to the source of the Nile, in 1980

- Operation Lifeline Sudan, the first years in pictures

- East Coast – West Coast, across the USA

- New York - A Walk on the Wild Side

- Into the Midnight Sun (Journey to the North Cape)

- The Door to Hell and the Path to Health (Turkmenistan)

- Mud Volcanoes and Candy Cane Mountains (Azerbaijan)

- Magic South (Southern Africa)

- Azhdahak (from Germany to Armenia, by road)

- Top of Mexico

- At the edge of the bog - where we live

- Rudaki, a Wedding and Proto-Urban Sarazm (Tajikistan)

More Insights from Outside the Bubble, by Detlef Palm

Detlef can be contacted via detlefpalm55@gmail.com

The good old days, how different from writing integrated, rights-based frameworks.

ReplyDeleteNo wonder the PPP was so good - the roots you put down in Somaliland obviously made you question Book D for a re-think. This is a great story. I was waiting to here about Camel fat being stuck in your beard? Even your last post as Rep - I could always "hear" the practical voice of the fleet manager coming through. LIkewise in audits. Very few UNICEF start their careers this way anymore - and it shows. I met someone the other day who just walked into UNICEF as a P3 having done a masters and a few years of work helping the university and a network of NGO organise a youth campaign. Not a day in the dust. Old time UNICEFers used to say: Boots on the ground and head at the table of government. Meaning we kept our boots dirty in the field and used that to influence government on behalf of children. If you read programme monitoring visit reports - they are rarely about results and often about cutting a ribbon or launching a framework. I wonder how many frameworks it takes to give a child a good start?

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteCoincidentally - in every single one of my postings in UNICEF the past couple or so decades we have asked the elusive question of ourselves concerning the "jointness" or "integrated-ness" of our work. There are legendary examples of this - but rarely if ever do we have evidence we actually did this and if it made an impact. There was JSP in Southern Tanzania - the legend of Urban J and the seed of the nutrition model. I arrived in a new post few months ago - and this is THIRTY years after your start on the "integrated" approach of NWISDP in Somaliland - and we are STILL asking ourselves the same basic question: a child cannot be cut in pieces - so why do we programme in a piece-meal manner and scatter our resources? Some WASH here, some baby measuring there, some vaccine there, some teacher training there - yet we cannot seem to plan in an integrated manner or each a child with all services - we just keep doing the same things for decades on end. Why are we unable to focus ?

ReplyDeleteThank you Detlef for sharing such an interesting, challenging, probably one of your most important part of life. Going through such experiences for years changes ones view on the happenings going on in our world.

ReplyDeleteDetlef, I had some similar experiences with SCF where I worked for 2 years in 1981/2 in Derbi Xoore and Dare Ma'ane. This includes being rudely woken up at 5 a.m. while sleeping on the beach by a US marine beach invasion - no red smoke in our case but they did invite us for lunch on one of their ships. Lots of fun even if the food was better in downtown Berbera than on the ship. I also used to drive up and down from Boroma to Djibouti and also lost a wheel of a Land Rover (in my case the lug nuts sheared off) and had to tie it back on with rope I luckily had in the car. You must also have marvelled at slick hairstyle and grumpy nature of the Djiboutian chief border control officer at Lawyacado too. And I think I recognise one of the muddy photos of being on that stretch close to the Tug outside of Zeila (did you make friends with the District Commissioner in Zeila? Quite a fun guy who arranged an overnight trip to that island just off Zeila). This happened just after we gave all our water to a 10 year old pastoralist who asked for some water by the side of the road. I also worked and played with Chris Bentley - we pioneered primary health care outside of the refugee camps, mainly soccer in our case - we weren't much good being rugby players. We also had Toyotas and Land Rovers and found the former seemed to be indestructible. We never had a borehole drilling machine. We relied on Oxfam provided solar panel powered water pumps - possibly one of the earliest uses of solar powered pumps in East Africa.

ReplyDeleteThanks Detlef for aother ascinanting report. It's amazing how you were abele to function in such difficult situations and even managed to raise a family, The children certainly got the best education there imaginable.

ReplyDelete🙏Detlef. Interesting for me since I was in Mogadishu with Stuart McNab & Phyllis Gestrin is the full name. Every Tuesday evening Stuart, Rolf, Marie and Per& I- went with many others out in the desert for Hash runs. We also built a small shed on the beach and during weekends we overnighted and during the day we wind surfed doing our best to avoid the sharks. Unfortunately my successor’s daughter didn’t have that luck. That’s the reason maybe that the beach was named Shark’s Bay! I’m now in safe Sweden. Rolf & Marie passed away last year. Sadly also Stuart. Jorgen G. Andersen

ReplyDeleteFantastic collection of photos and good reporting. Thank you for you for sharing :)

ReplyDeleteDetlef, your and Roger Pearson's experience with US Marines landing on foreign shores brought back a similar memory. In 1958, before I joined UNICEF, I had a temporary job at MASCO (Middle East Aircraft Maintenance Company) which was the most important centre for aircraft maintenance and repair in the Middle East region based in Beirut Airport. I was one of a small group of "planners" who were responsible for scheduling all Middle East Airline's fleet of planes. We had 24 hour coverage and worked in shifts of twelve hours (7 am to 7pm, and 7pm to 7 am). I chose the late night shifts as this gave me time during the days to search for employment.

ReplyDeleteOne night at about 5am. when it was quiet my colleague and I went for a smoke break, and walked down to the beach

(the airport was virtually next to the shore). As it started getting a bit lighter we noticed a lot of strange ships getting close to the shore and before we guessed what was going on we saw a bunch of military personnel running ashore from the craft . A few saw us, came close, and one huge marine shouted at us, "where are they?" in English. We answered, "who?", and he replied, "the Arabs". My buddy and I looked at each other, smiled and told the marine, " we are both Arabs, but what are you doing here in battle fatigues?". It turned out that the Lebanese President who was worried about a small civil conflict from becoming unmanagable, had asked President Eisenhower to send his marines to "stabilize" the situation in Lebanon. Ultimately, the marines set up camp a bit to the north of the airport and we became friendly with some of them, drinking beers, and even playing softball with their teams.